The Hidden Reason ARFID Therapy Isn’t Helping — And How to Truly Heal Mealtimes

When You’re Doing Everything Right… and It’s Still Not Working

You followed the advice. You got the evaluations and they said it was ARFID. You sat through appointments. You showed up, week after week, to feeding therapy sessions. And yet—your child is still barely eating. You’re watching other families graduate from treatment while you’re stuck in survival mode, wondering:

Why isn’t ARFID treatment working for my child?

First, I want to say this as clearly as I can: It is not your fault.

You are not a failure, and your child isn’t broken.

If you’re reading this, you’re a parent who deeply cares. You’ve invested time, energy, and probably a lot of emotion into trying to help your child. And when things aren’t improving the way you hoped, it can leave you feeling defeated, even hopeless.

But here’s the thing most parents don’t get told: if ARFID treatment isn’t working, it’s often because something crucial is missing. Not because you didn’t try hard enough.

Let’s look at what’s usually offered—and what’s often left out.

What Traditional ARFID Treatment Often Includes

Many families are referred to a psychologist or mental health provider for ARFID therapy. This is usually based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for ARFID (CBT-AR), a structured, short-term approach that focuses on helping children:

Identify their fear or avoidance around food

Create a hierarchy of feared foods

Practice exposures while learning coping strategies

Develop motivation and autonomy around eating

CBT-AR can be incredibly helpful for some kids—especially those who are cognitively able to reflect on their thinking, tolerate structured exposures, and don’t have other complicating factors like sensory processing challenges, gut issues, or oral motor delays.

But for many children, especially those with complex developmental profiles or a history of trauma around feeding, psychological therapy alone isn’t enough.

Here’s why:

1. CBT doesn’t address physical barriers to eating.

If your child has poor oral motor skills, a tongue tie, chronic constipation, or food intolerances, no amount of mindset coaching will make eating feel safer. Children aren’t avoiding food because of faulty thinking—they’re avoiding it because their body is telling them it’s not safe or comfortable.

2. It assumes your child can verbalize their thoughts and emotions.

CBT works best when kids can express what they’re feeling and why. But many children with ARFID are young, neurodivergent, or have limited insight into their own internal experience. They might not be able to say, “This food makes my stomach hurt” or “I’m afraid I’ll gag.” So therapy can become performative rather than effective.

3. It still puts pressure on food exposures.

While CBT-AR is supposed to be child-led, it often still revolves around food hierarchies and exposure-based goals. For some children, especially those with a trauma history or deep nervous system dysregulation, this can feel like pressure—even if it’s gentle. That pressure can reinforce fear instead of dissolving it.

4. It often overlooks the parent-child dynamic.

CBT-AR focuses primarily on the child’s internal thought patterns, with limited involvement from parents beyond being “coaches.” But when a child is in survival mode around food, the most effective healing often comes from co-regulation—where the parent learns how to shift their own mindset and nervous system first, so the child can feel truly safe.

So What’s the Alternative?

Let’s pause for a moment and clear something up:

Many children labeled with ARFID don’t actually have ARFID.

They may be fearful of food, yes. They may avoid eating. But fear-based avoidance isn’t always rooted in anxiety or distorted thinking—which is what the ARFID diagnosis is supposed to capture. Instead, their food refusal is often a response to a physical, sensory, or skill-based barrier that hasn’t been properly assessed.

This is where the diagnosis of Pediatric Feeding Disorder (PFD) is often more appropriate.

PFD is a medical diagnosis that reflects a breakdown in the child’s ability to eat due to one or more disruptions in the following domains:

Medical (e.g., reflux, allergies, GI inflammation, constipation)

Nutrition (e.g., poor growth, nutrient deficiencies, limited variety)

Feeding skills (e.g., chewing, swallowing, oral motor coordination)

Psychosocial (e.g., family stress, past trauma, mealtime conflict)

This framework aligns beautifully with what I call the Four Pillars of Feeding—gut health, sensory processing, oral motor skills, and mindset.

In contrast, ARFID is a psychiatric diagnosis based on:

A persistent failure to meet nutritional/energy needs

Food avoidance that isn’t explained by body image concerns

Significant interference with psychosocial functioning

It’s often treated through a mental health lens, but that lens is not enough when the root of the problem lies in the child’s biology, development, or environment.

If your child is being treated for ARFID through a psychological approach (like CBT) and it’s not working, it may be because your child’s challenges aren’t just psychological.

They might not have ARFID at all.

They might have PFD that’s showing up as food fear—but if we never address the real issue (like pain, motor fatigue, gagging from texture, or poor gut health), the fear will remain, and no amount of talk therapy will “fix” it.

This is why I always emphasize a whole-child, whole-body approach.

Why Behavior Alone Isn’t Enough

(And Why ABA-Based Feeding Therapy Misses the Mark)

A lot of feeding programs — especially those marketed toward children with autism or extreme picky eating — are grounded in behavioral principles. These approaches use rewards, consequences, and repetition to increase “compliance” with eating. They often follow Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) models, where the goal is to increase desired behaviors (like accepting bites of food) and extinguish undesired ones (like food refusal, gagging, or avoidance).

The problem?

Eating is not a behavior to be trained. It is a developmental, sensory, emotional, and relational experience.

Trying to reinforce eating without understanding why a child refuses food is like trying to bribe someone into lifting a heavy weight with a sprained back. They may force themselves to do it for a reward—but the injury is still there, and now they also associate pain and pressure with the experience.

Here’s why ABA-based feeding approaches often backfire:

1. They ignore the child’s internal experience.

If your child has real pain (from reflux, constipation, or oral motor fatigue) or sensory distress (from texture, smell, or visual overwhelm), behavioral methods don’t make those experiences disappear. They just teach the child to suppress their responses—which can lead to shutdown, trauma, or even long-term food aversion.

2. They treat eating as a compliance task.

ABA approaches often measure success by how many bites a child takes or how long they tolerate food on a plate. But real feeding success isn’t about compliance—it’s about connection, curiosity, safety, and regulation. When children feel safe, they naturally begin to explore and expand their diet. When they feel forced, their nervous system goes into survival mode.

3. They use external rewards, not internal motivation.

Feeding should be intrinsically motivated. Children should eat because they feel hungry, curious, or connected—not because they want to avoid a negative consequence or earn a reward. When food becomes transactional, children can lose trust in their own body signals—and in the people trying to help them.

4. They often fail to create lasting change.

Some children may “perform” well in therapy sessions but go right back to food refusal at home. Why? Because the environment may change, but the root cause hasn’t been addressed. Real progress comes when we support the whole child, not just shape the behavior.

It’s natural to want to help your child “learn” to eat. But behavior-only models assume that food refusal is a choice, when in fact, for many children with ARFID, it’s a protective response.

Trying to change a behavior without understanding why it exists is like trying to fix a leaky roof by mopping the floor. You’re dealing with the symptom, not the root cause.

For example:

If your child avoids crunchy textures because they have poor jaw strength, repeated exposure will only cause frustration.

If they avoid food because of gut pain, exposure therapy can reinforce a negative relationship with eating.

If their sensory system is overwhelmed by smells and textures, they won’t be able to stay regulated enough to participate in a meal, no matter how many times they’re told to “just try it.”

This is why many families spend months in feeding therapy with little change—because the approach is asking their child to climb a ladder with missing rungs.

What’s the Alternative?

We don’t need to “train” children to eat. We need to understand what’s getting in the way — and remove those barriers with compassion and evidence-based support.

This means:

Looking at gut discomfort, not just refusal

Supporting oral motor skills, not just asking for bites

Respecting sensory boundaries, not forcing tolerance

Teaching self-regulation, not demanding compliance

Building trust, not enforcing control

This is especially critical if your child has been through multiple therapies and still isn’t making meaningful progress. If they’ve been praised for taking one bite of cracker but still can’t sit at the table without panic — that’s not success. That’s survival.

And survival is not the goal at Foodology Feeding; Thriving is.

Who You Work With Matters

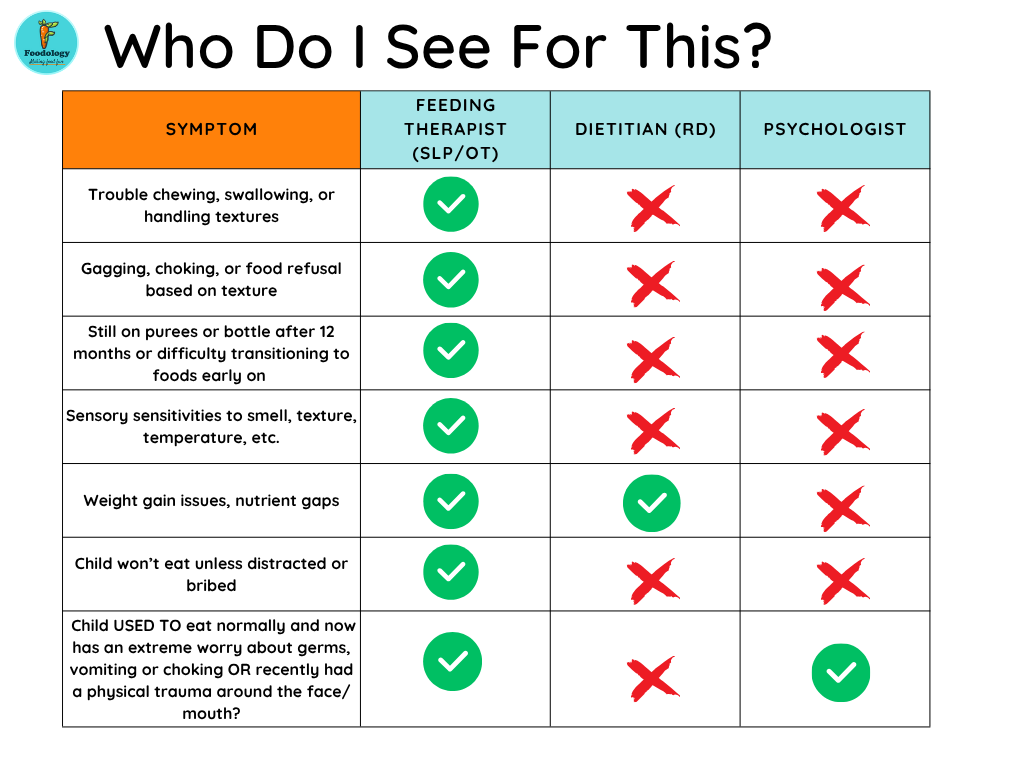

Many families are referred to a psychologist for ARFID treatment—but not all ARFID cases belong in a psychologist’s office.

Before pursuing mental health-based treatment, your child should be evaluated by a feeding therapist with training in:

Oral-motor function

Sensory processing

Gut and medical contributors to feeding issues

Why? It’s imperative to understand the origins of their issues and what you actually need to work on. For example I see a lot of dietitians promoting their picky eating courses. Dieticians are great at a lot of things, they can even help a bit with mindset! BUT they don’t have background to evaluate oral motor skills or sensory issues. And I hear of a lot of kids getting behavioral therapy at a psychologist office for ARFID, but a psychologist can’t determine if their issue is beyond food trauma, so they may be treating the child in the wrong way. And seeing any SLP or OT won’t cut it either. There are no graduate programs for SLP or OT that provides the training to cover all the bases. You need to seek someone who has gone above and beyond their schooling to learn more about this extremely complex subject before just handing over your insurance card. It’s easy to go with the local clinic that takes insurance, but if they treat everyone they specialize in no one, and you TRULY need someone who specializes in this unique area to help if you want to see true progress and changes.

What Real Healing Looks Like: A Case Example

Let me tell you about Maya (name changed), a 6-year-old girl with a long list of feeding struggles. She had been in feeding therapy for over a year. Every session focused on exposure—look at the food, touch the food, smell the food, lick the food. Maya complied, but she rarely ate. Her mom described her as anxious, sensitive, and “always wired.”

We took a step back and looked at Maya’s full picture:

Her stool tests showed signs of gut inflammation.

She had a tongue tie and weak jaw muscles affecting her chewing.

She was overresponsive to sound and texture, especially wet foods.

She had high anxiety around change and a history of vomiting after meals.

Through the Personalized Mealtime Roadmap, we built a plan that worked on each of the Four Pillars:

We partnered with a functional practitioner to support gut healing.

Maya did oral motor exercises and had her tongue tie addressed.

We integrated gentle sensory activities and restructured her environment to reduce overwhelm.

Most importantly, we taught Maya and her mom tools to calm their nervous systems before meals, shifting from pressure to curiosity.

Within three months, she went from a handful of accepted foods to engaging in meals, tasting new foods, and even requesting one of the fruits she used to gag at.

Real healing doesn’t look like coercion or compliance. It looks like safety, connection, and capacity.

A Different Way Forward

If you’ve been wondering why your child’s feeding therapy isn’t helping…

If you’re tired of watching your child go through the motions with no real progress…

If you feel like you’re managing symptoms instead of solving the problem…

It’s time for a different approach.

Your Next Step: Get Your Personalized Mealtime Roadmap

Every child with ARFID or PFD is unique. Their healing journey shouldn’t be cookie-cutter. That’s why I created the Personalized Mealtime Roadmap, a structured but flexible tool to uncover exactly what’s standing in the way of progress—so we can support your child from the inside out.

Inside the Roadmap, you’ll discover:

✅ How your child scores across the Four Pillars of Feeding

✅ Personalized strategies tailored to their needs and based on their unique personality and hard-hired tendencies

✅ A step-by-step action plan to build trust, reduce fear, and make real, sustainable progress at mealtimes

You don’t have to keep guessing—or doing more of what hasn’t worked.

Visit us here to explore your roadmap forward.

We’re here to help you move your child from food fear to food freedom—step by step, at their pace, with expert support.

You don’t have to do this alone. ❤️